Sunday, June 29 at 7 PM

ELLIOT’S CHOICES

FILM SCREENINGS

Navajo Talking Picture (1986. 45 min, directed by Arlene Bowman)

500 Millibars of Ecstasy (1989. 5 min, directed by George Kuchar). maybe

A Certain (Un)disclosed Illness (Elliott Jamal Robbins, 2024, 1 min 7 sec),

Wittgenstein, or God (Elliott Jamal Robbins, 2021, 23 sec),

John Wayne Code (Elliott Jamal Robbins, 2 min 44 sec)

Sunday, June 22 at 7pm

Un Chant d’Amour (1950, 26 min, directed by Jean Genet)

Jean Genet: An Interview with Antoine Bourseiller (1981, 50 min, directed by Antoine Bourseiller)

ANNOUNCEMENTS

Sunday, June 22nd at 7pm:

Every Sunday starting June 22 (7pm), we will screen a series of films titled Elliott’s Choices that reflect the themes of his exhibition Feats of Strength. Elliott and the gallery will begin with Jean Genet’s only film, Un Chant d’Amour (1950, 26 min), followed by Jean Genet: An Interview with Antoine Bourseiller (1981, 50 min).

The idea began with a conversation between Elliott and me about what might constitute a universal feeling—that rare moment when it seems a coincidence to encounter someone who truly understands what you're trying to express. That, and how at least for me, I’ve always struggled with the concept-of-the--process of exhibition-making—namely, the tension between articulating a solid curatorial message with clarity and elegance about what the works mean or simply show, versus focusing more on the creative process of the artist, where capturing the process itself becomes the aim. Of course it can be either but for just a bit of time I'm far favoring the latter. I don't want to see shows with unified aesthetics or standalone conceptual objects, and such ilks, because they often feel like products, driven by results, whether organized from peacock looking curators or swashbuckling art dealers with artists who are not necessarily victims as they are certainly not saints. Most art works are titled after they are made, I think. There is always the invisible dialogue that feels correct at the very least.

What I’ve always resisted is applying theory in a “top-down” way, where art becomes a vehicle to illustrate preexisting ideas. Maybe this is due to my background in philosophy — and maybe it’s a too-specific complaint — but I’ve always believed that generating theory from the artwork itself is far more difficult, and far more worthwhile. It requires an awareness that theory is merely a tool for understanding — not a belief system to be worshipped. Otherwise, the art risks becoming either expositional text, or worse, an ideological puppet. Or even worse still: a pretentious affect, where the work is used to enlighten an audience that already considers itself enlightened.

It reminds me of a certain kind of “bootleg ivory tower” mentality — a conviction that theory makes reality more complex as a way to respect it, when in fact most scholastic frameworks assume that reality is already too complex, and simplification is a necessary tool. In that sense, aspirational elitism seems to me one of the more insidious cultural threats — with real, determining consequences.

We also spoke of our shared admiration for certain artists and societies—across literature, film, and the art world—that acknowledge, or at least attempt to outline, the limitations of their respective practices, transforming such constraints into enabling forces. Jean Genet naturally came up: a vanguard writer we both deeply respect and honor. And of course, there’s Un Chant d’Amour. Let’s begin:

Set within the confines of a prison, Un Chant d’Amour follows two inmates who wordlessly express longing for one another through walls, gestures, and tobacco smoke, under the watchful eye of a voyeuristic guard. The film was banned for decades due to its open depiction of male intimacy. Considered obscene at the time of its release, it was rarely shown publicly.

Today, it stands as a landmark of both avant-garde queer cinema and film itself, a defiant expression of desire under constraint, cloaked in the veneer of smoke, kisses, and surveillance. It is our first choice for its direct resonance with the film Fantasmagorie.

It will be followed by Jean Genet: An Interview with Antoine Bourseiller (1981), in which Genet reflects on his storied life and its entwinement with his evolved relationship to art-making, spanning over a half decade in his involvement with refugees, gay liberation, world war 2, the Black Panthers, and a series of essays reflected with non-linear time, but all veered back to himself, of which he ping pongs between his idealized self and his actual life.

Other considerations include a number of great shorts, long-form works, clips, and interviews in the film medium that reflect themes inspired by Elliott’s thinking and practice: Navajo Talking Pictures (1985), a journey that denies cultural explanations while stalking the grandmother who doesn’t want to be filmed—a lesson about failure in art; experimental animation and collage, where characters face the fourth wall only to realize there are no walls (Susan Pitt, Aeon Flux, Anger); alienation/hiding/(anti)performance (Don’t Answer Me, Mitski, D’eux, The Exiles, Mod Fuck performance); Queer Desire (Pink Narcissus, Riggs, Pitt, Fassbinder); or cinema as memory, longing, or awful cultural critique.

More to be announced!

Sunday, June 29th at 7pm

We continue the second iteration of Elliott’s Choices this Sunday and every Sunday until the conclusion of his exhibition. Each session includes films selected by Elliott himself, followed by some of Elliott’s own films and a discussion with the audience over Zoom.

Last week we screened Jean Genet’s Un Chant d’Amour (Jean Genet, 1950, 25 min) and An Interview with Jean Genet (Antoine Bourseiller, 1981, 55 min), followed by Elliott’s own film Fantasmagorie (ibid, 2025, :53 sec). Our discussion explored the ways in which Genet never seemed to claim understanding or possession over the people he desired, especially revolutionary resistance fighters. Rather, he truly witnessed them in all their contradictions, refusing to idealize them morally, even when he did so aesthetically, and even then, remaining critical of aesthetics itself. As Edward Said writes in his introduction to Prisoner of Love, “Genet made no claim of special insight or understanding, only the desire to be near, to witness, and, perhaps most importantly, to serve.”

Was Genet morally serious? Absolutely. But not in the Victorian sense of self-righteous honor and shame in service of a conservative order. His seriousness came from a radical willingness to give himself over to struggle and resistance, even when his gaze remained partial and complicated.

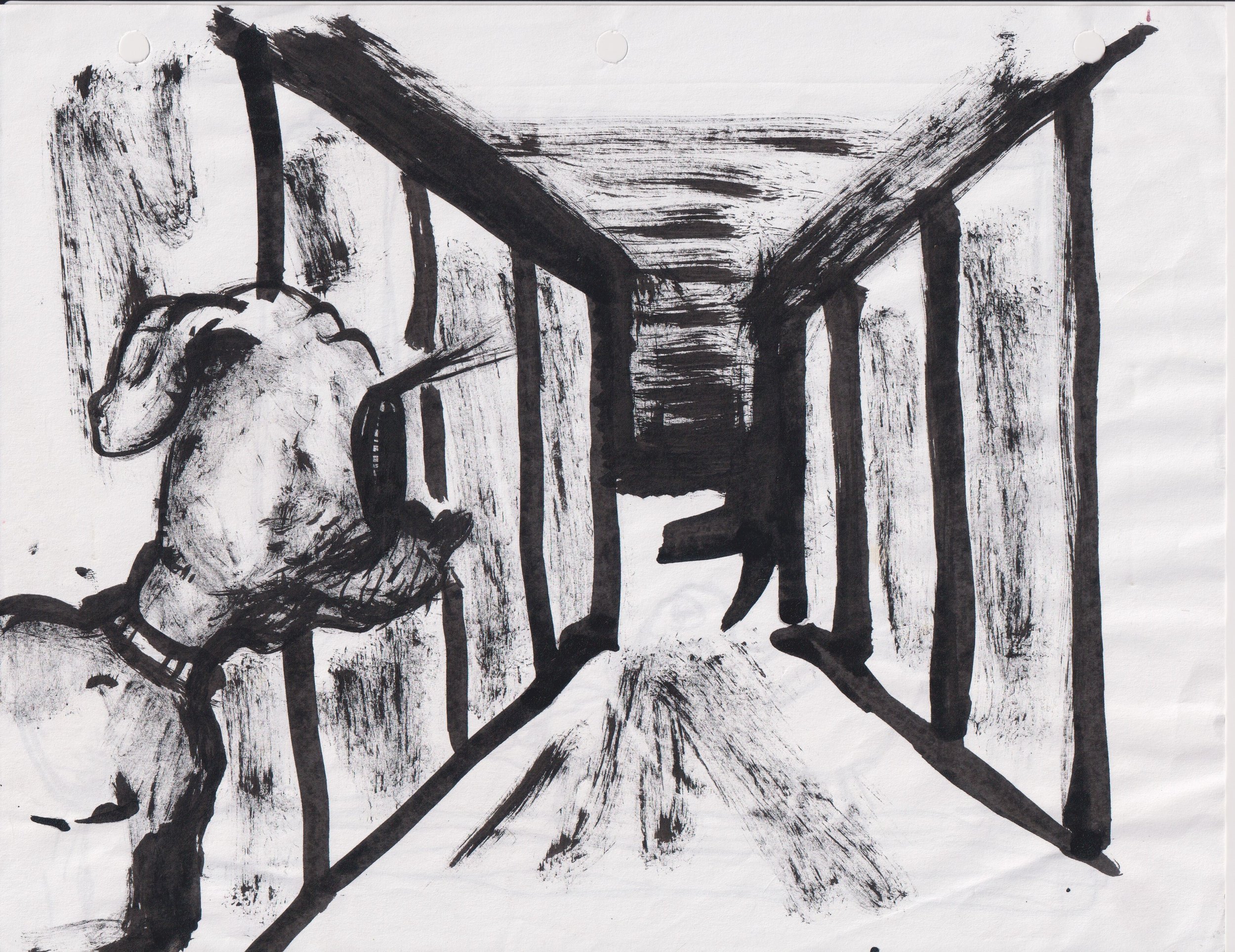

From there, we turned to Elliott’s own use of portals: illusions that fade or blink, televisions, doors in the desert, highway signs. Spectral things that feel like entrances, often framed by the long expanse of a hallway, always capturing the protagonist’s attention, like this:

For this iteration, we’ll be showing selected documentary films that explore the active role of the camera and gaze, as well as fractured narratives of the self. We’ll begin with Navajo Talking Picture (1986), the landmark film by Arlene Bowman, a Navajo filmmaker raised outside the reservation. Bowman documents her attempt to reconnect with her grandmother and heritage—but none of that is achieved. Her grandmother literally flees from the camera, as if stalked. The film purposefully breaks from romanticized ethnography aimed at audiences seeking cultural enlightenment. Instead, Bowman reveals the power of awkwardness, resistance, and contradiction that comes with being an outsider trying to reclaim insider status, and most of all, the bittersweet, sublime horror of failure in the art-making process.

Next, we’ll screen George Kuchar’s 500 Millibars of Ecstasy, and perhaps another from his Weather Diaries series, in which he chases storms across Oklahoma while holed up in cheap, rackety motels in desolate places. Over weeks at a time, he catalogs his daily existence—television, telephone, junk food, indigestion—suffused with eroticism, comedy, and self-reckoning.

We’ll also include Jeff Keen’s Marvo Movie (1967, 5 min), a chaotic sensory collage of Brighton beach, war footage, pop ephemera, and comic absurdity that feels like it was edited with a stun gun.

We’ll conclude with a few of Elliott’s very short loops, including A Certain (Un)disclosed Illness (Elliott Jamal Robbins, 2024, 1 min 7 sec), Wittgenstein, or God (Elliott Jamal Robbins, 2021, 23 sec), and John Wayne Code (Elliott Jamal Robbins, 2 min 44 sec), which makes extensive use of collage and is as much about the making of film as it is the unmaking of it—followed by a conversation with the artist himself, live from his home in New Mexico.