Lucky DeBellevue

"assignment"

09/18 - 11/06

Opening reception: Sunday, September 18th (6-8pm)

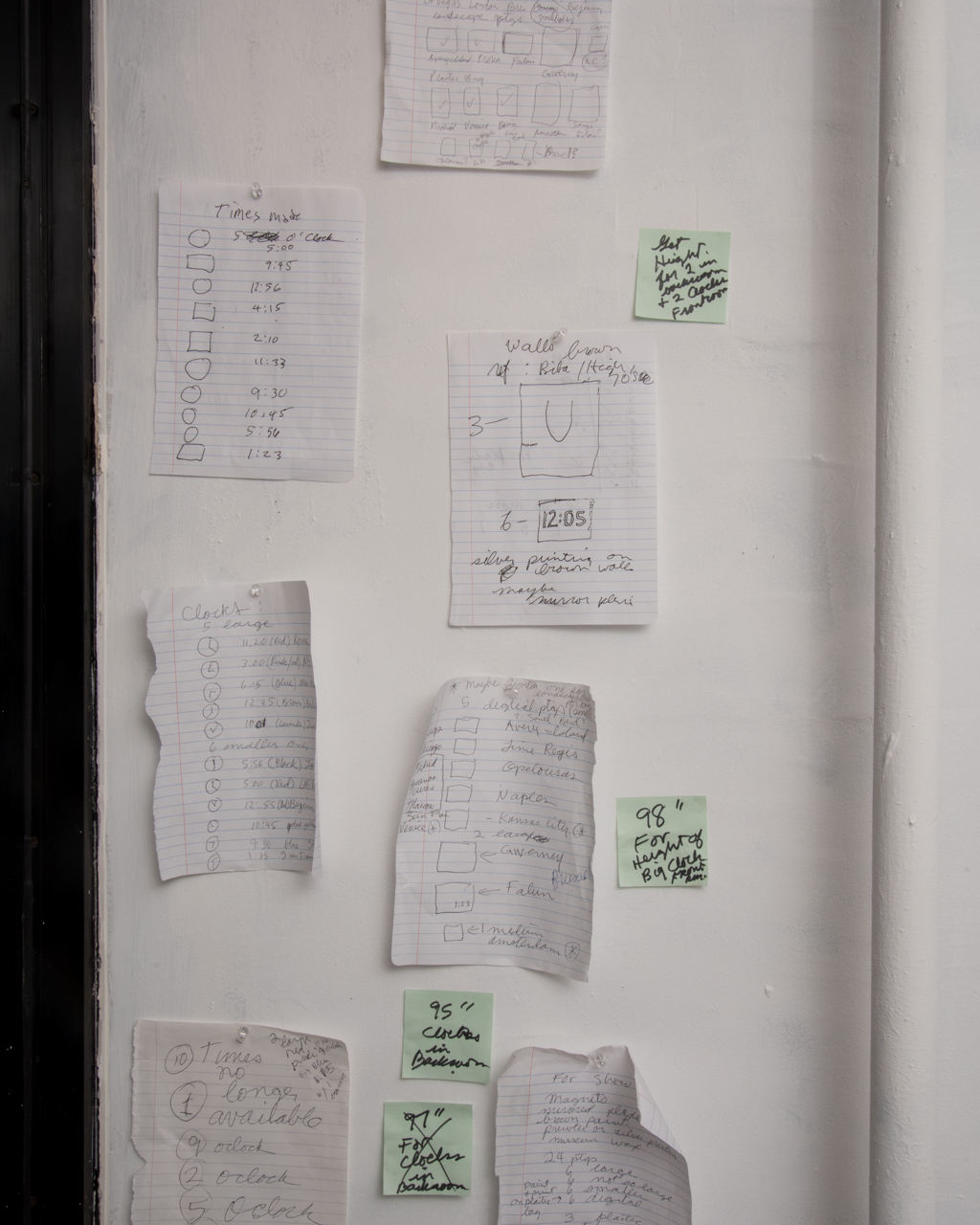

What does an artist choose to make? What is actually realized from the many ideas that float around in someone’s head? Lucky DeBellevue asks this question in his second exhibition titled "assignment" at Kai Matsumiya where over 400 drawings depicting various ideas and projects spanning a twenty-year period will be shown, and “time-based” works – in the literal sense – that encapsulate all space, time, locales, processes, and idea-formations in the life of the artist.

Most of the drawings in the show are for projects that remain unrealized. They depict ideas for non-profit spaces, a permanent sculpture at a university, a private commission for a collector’s home, museum installations, and gallery exhibitions. They run the gamut from personal archetypical shapes that appear and reappear, a collaborative proposal for an airport that stipulated a “western” theme that was not successful, and technical instructions for installing a larger sculpture at a museum. Reflecting on these processes of thought and engagements, most of which never came to fruition, DeBellevue sees his engagement with the artistic process as very similar to the way Maggie Nelson describes her writing process in her book The Argonauts:

“Most of my writing usually feels like a bad idea, which makes it hard for me to know which ideas feel bad because they have merit, and which ones feel bad because they don’t. Often I watch myself gravitating toward the bad idea, as if the final girl in the horror movie. … But somewhere along the line, from my heroes, whose souls were forged in fires infinitely hotter than mine, I gained an outsized faith in articulation itself as its own form of production.”

While this “outsized faith in articulation” is present in the drawings, whether realized or not, the other works in the exhibition speak to the relationships forged from that history of success, failure, good, bad, aversion, diversion, contingencies, determinations, confidence, and looming questions. Some of these drawings were ultimately rejected because of bureaucracies or political situations, others were never seen due to the many complicated idiosyncrasies that seize upon us in our everyday lives, some are celebrations of wonderments, and so on.

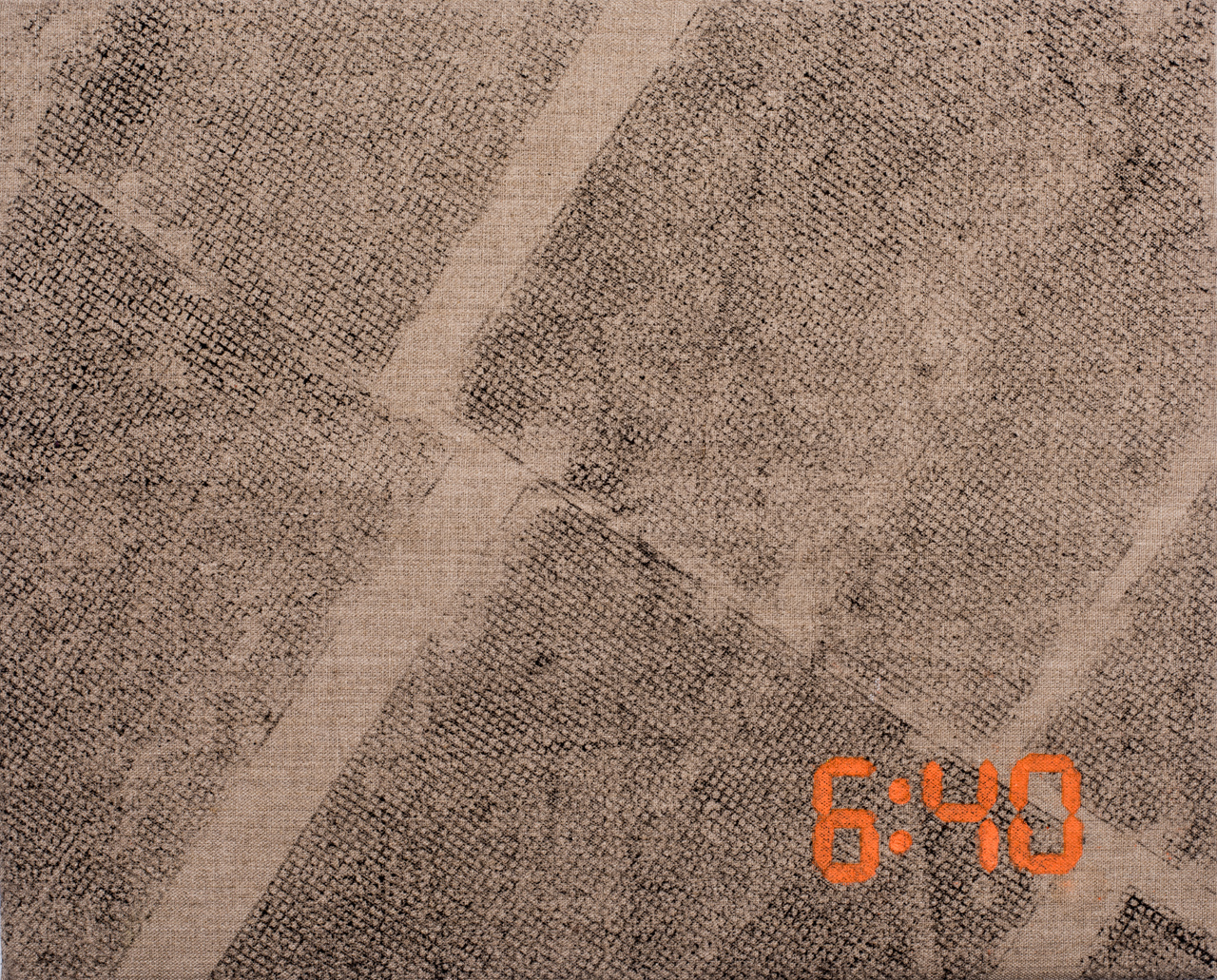

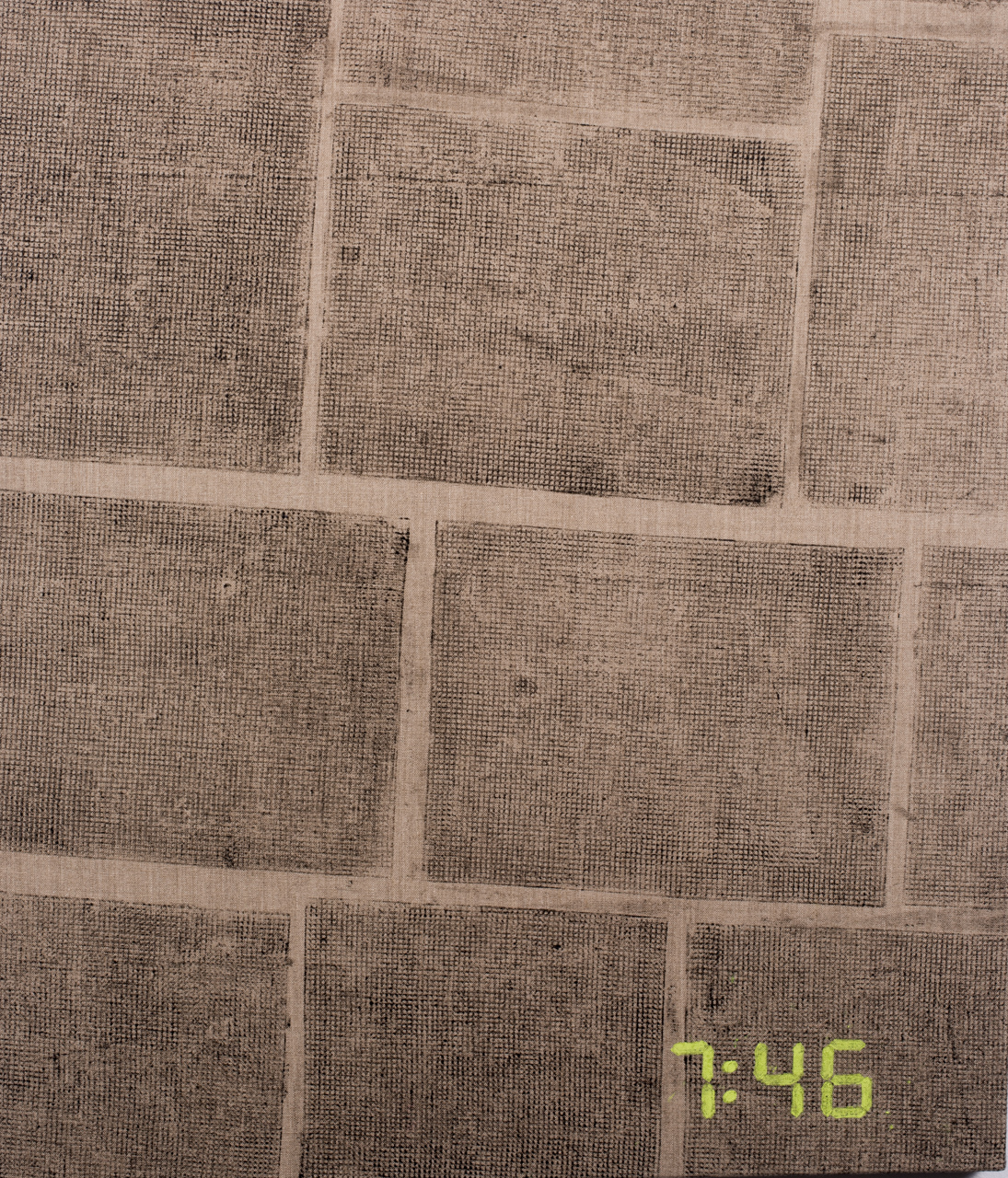

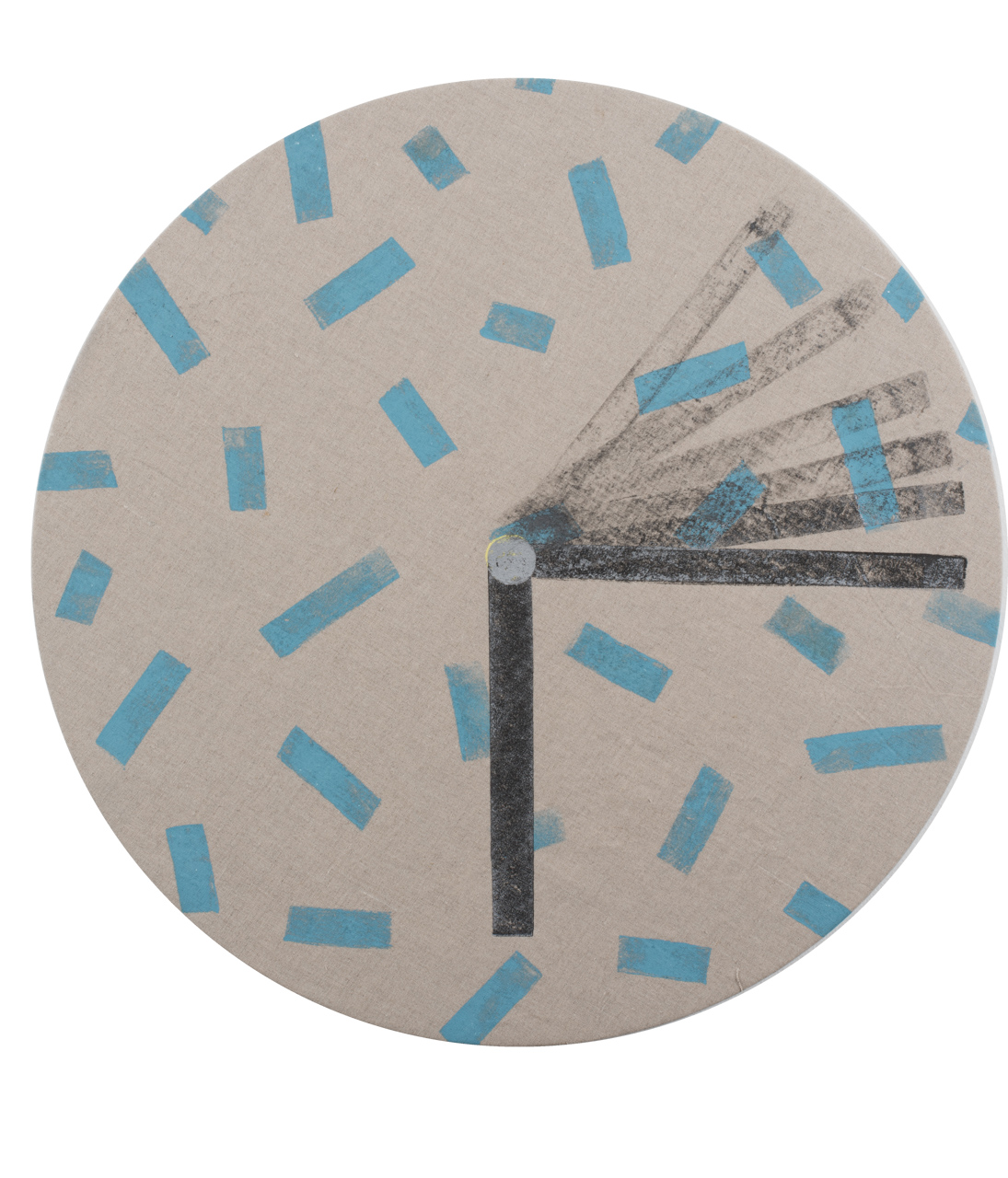

Integrated with these drawings are new time-based works. Each represents an hour of the day, and a location where DeBellevue’s work has appeared and is titled according to that location. These works may present themselves as “paintings,” but in fact are block printing ink on linen or mixed media works. DeBellevue uses the12-hour clock, and does not differentiate between AM and PM. Thus the viewer has their own point of reference as to what a certain time of day represents to them. For instance: 5:00. Is it the time one gets off work, or the time that one finally returns home after a marathon evening of partying? It is a mediation on time, of what can be made in the time allotted to us, the connotation of a certain hour of the day or night, and time simply lost.

The round-faced clocks hang high as they so often are in institutional spaces, an authoritative icon giving one guidance and information. Many of the clocks employ a trompe l’oiel representation of the minute hand moving forward, yet it is frozen within the moment. Some of the works are more abstract, referencing a screen, or an aerial view from a plane, with plots of lands divided by roads, and finalized with a digital time signature at the bottom right of the picture plane. The timed stamped photograph also positions itself as a signifier of a particular time in the rapidly changing history of technology. As a friend mentioned to DeBellevue, “whenever you see a time stamped photograph of someone on a dating website, you know it’s an old one.”

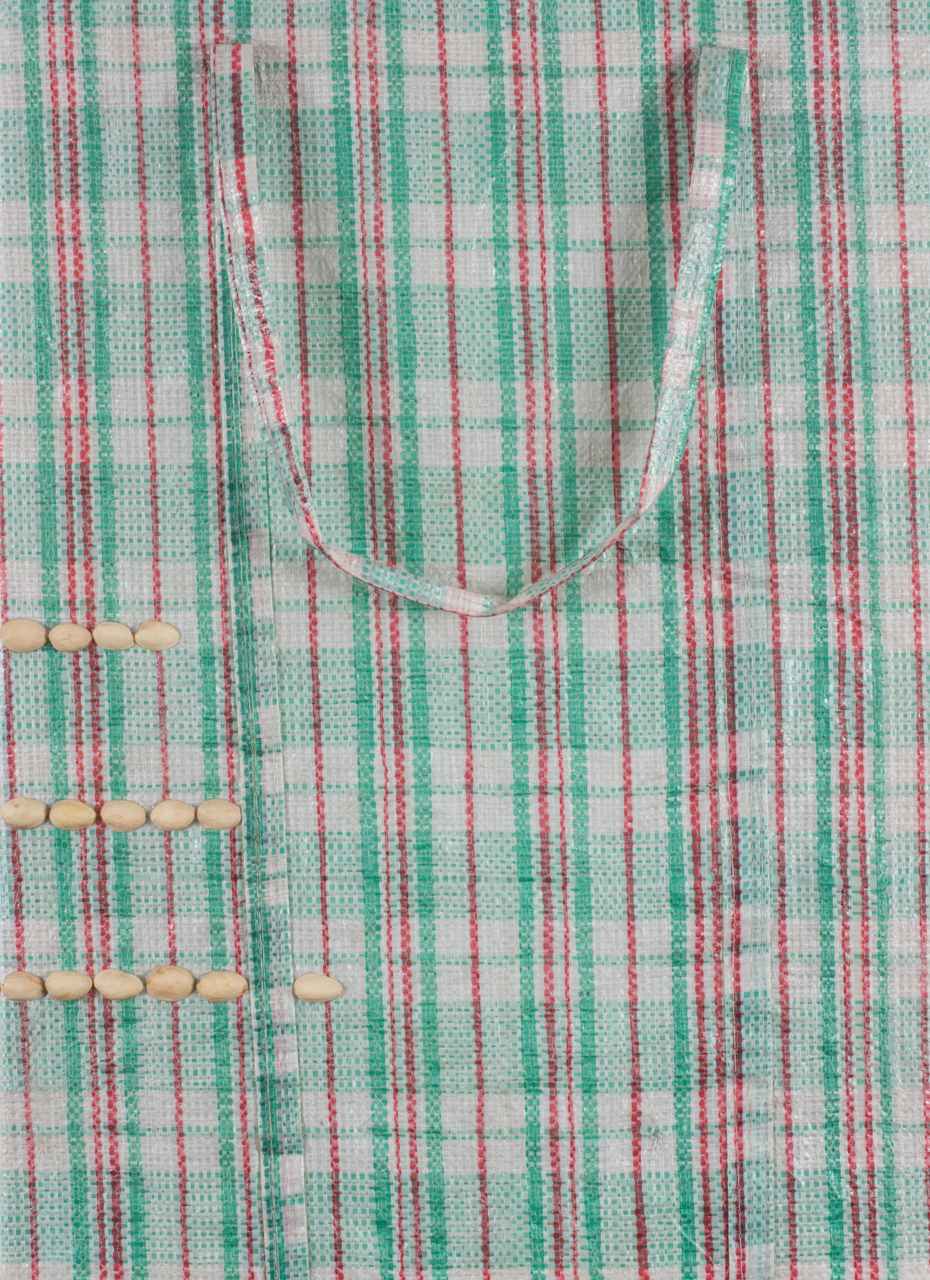

Finally, DeBellevue utilizes plaid plastic bags that urban dwellers from around the world recognize, and are presented over stretcher bars, with the carrying handles left intact, and a row of pistachio shells traveling across the surface. Each of the plastic bags in the exhibition has functioned as a utilitarian object in another context. The handle of each shows the aftermath of use. One functioned as a laundry bag in another life, another for transporting art supplies, and another to carry books from one place to another. Finally they are displayed as art objects at a gallery space. Each represents a particular activity at a particular time.

The title Assignment originates from a photograph sent to a DeBellevue by a relative who had recently cleaned out their attic in Lousiana. The image was of a self-portrait DeBellevue had painted in college, an assignment given by the professor. He then realized that working as an artist is also about finishing a series of assignments: some of which are institutional, and some of which are self-assigned.